A Lecture on Nothing

- Home

- Festival

- 2020-and-before

- Articles

- A Lecture On Nothing

- By:

By: Anders Beyer,

November 26, 2017

Close to 70 years after its world premiere: Robert Wilson’s version of John Cage’s famous “Lecture on Nothing” awakens the Chinese audience's interest in their… mobile phones?

Travelogue by Anders Beyer, Shanghai

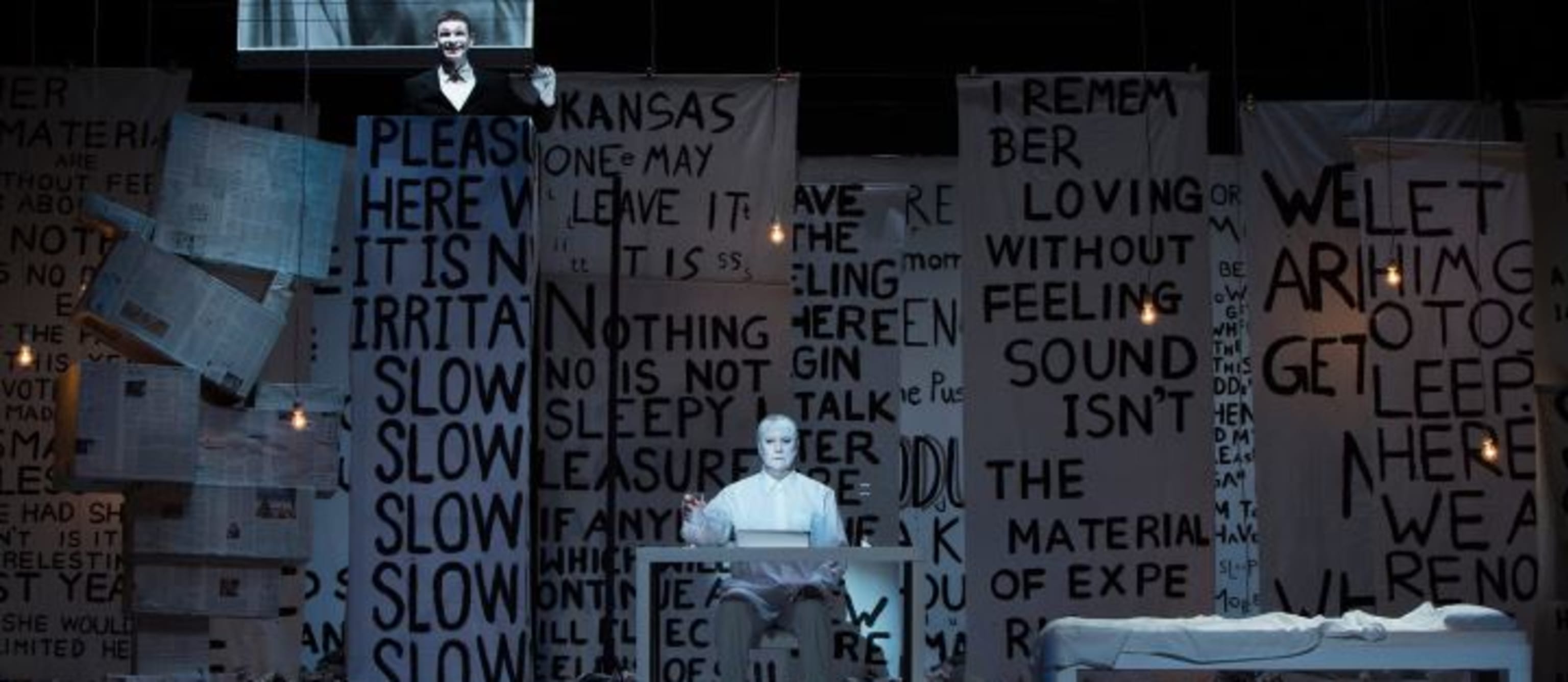

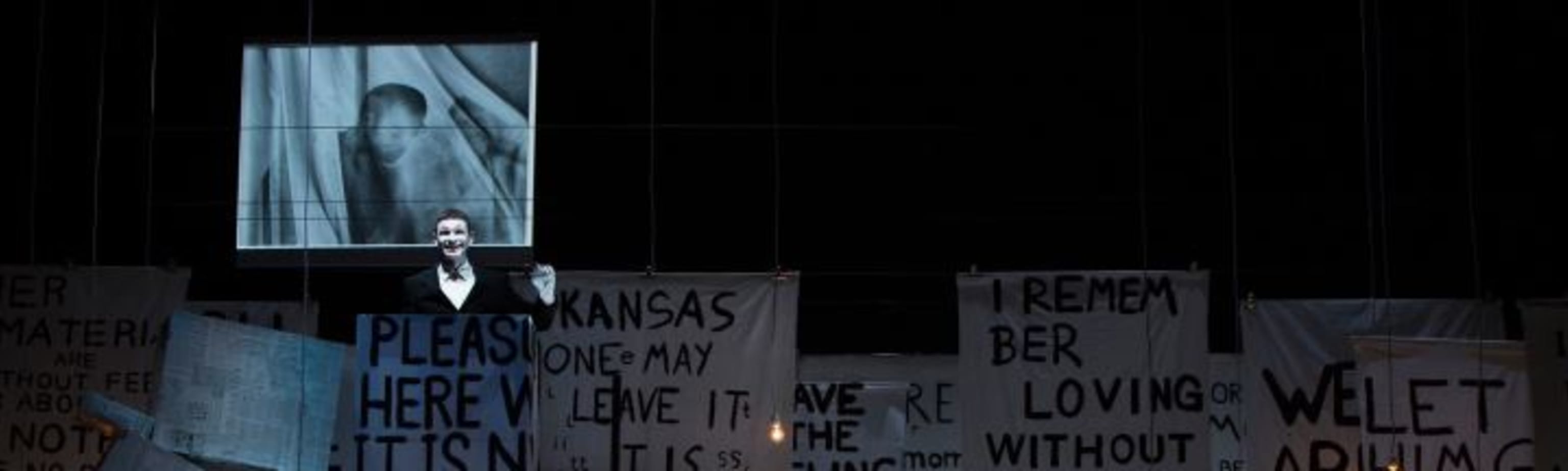

Shanghai Grand Theater. The lights go down in the auditorium. The performance begins. The legendary director Robert Wilson is sitting in the middle of the stage, dressed all in white. Several minutes pass, not a word from his mouth. Wilson opens the staged version of Cage’s renowned “Lecture on Nothing” with loud silence.

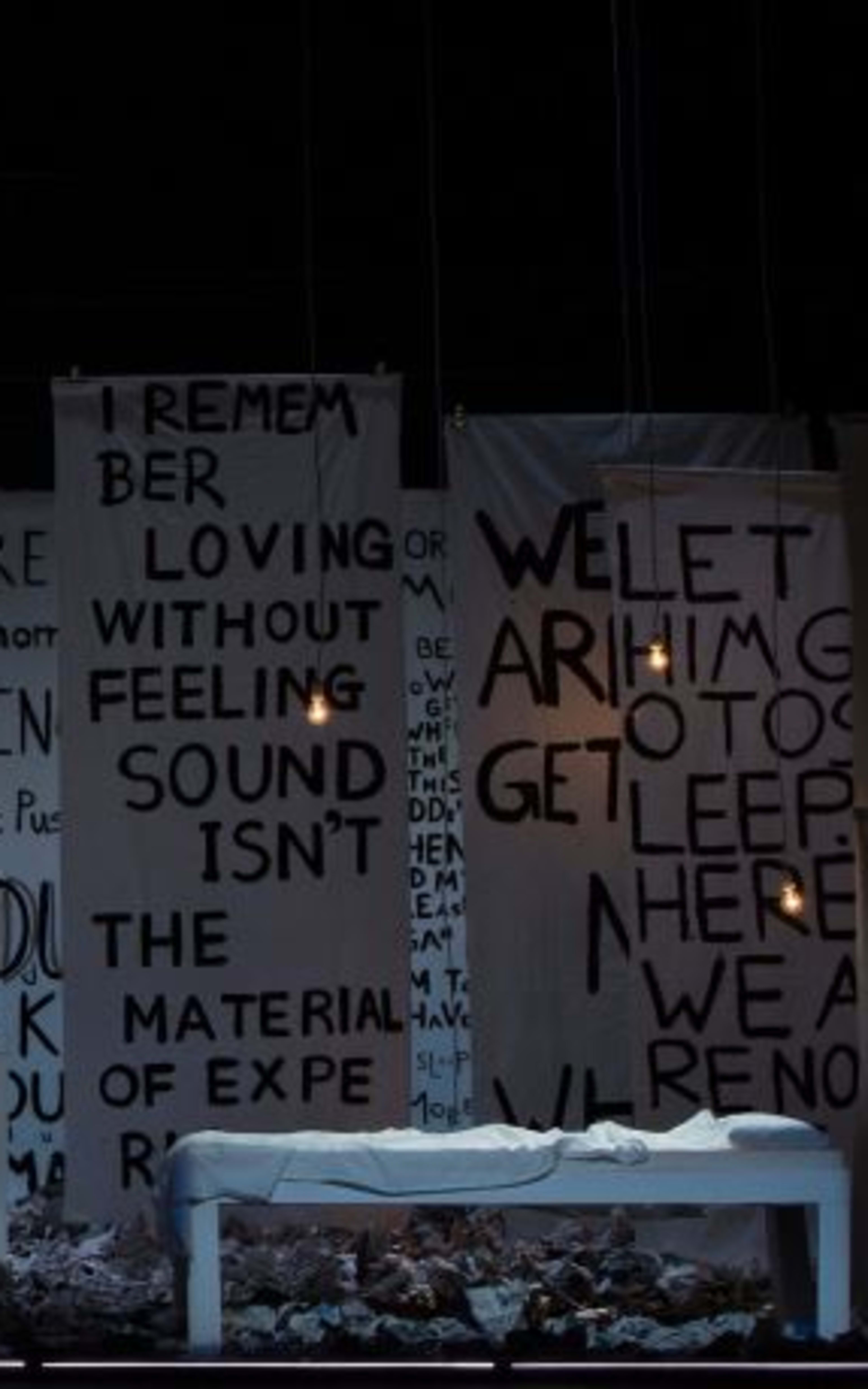

Suddenly, the theatre icon breaks the silence and starts the lecture. We are introduced to slow and intoned sequences of thought that undermine themselves once they seem to reach their point: “Slowly, as the talk goes on, we are getting nowhere and that is a pleasure.” It talks of how the actor has nothing to say, all the while saying just that: “I have nothing to say and that is the point of my saying it”.

In the preface to the book «Silence. Lectures and Writings by John Cage» (1961) where “Lecture on Nothing” was first published, Cage writes about the world premiere in Manhattan in 1949. There, the composer himself performed the 40 minute long lecture with seemingly endless repetitions that finally made a member of the audience, artist Jeanne Reynal, get up and shout on her way out: “John, I dearly love you, but I can’t bear another minute!”.

Later that evening there was a Q & A session on the performance. Regardless of the questions posed, Cage answered with one out of six pre-determined answers, one of which was «this was a reflection of my engagement in Zen».

In the staged version of “Lecture on Nothing”, Robert Wilson places the repetitive, musical prose in tableaux filled with magic that only Wilson is able to create. Overall, he loves repetition. In Norway, we witnessed this the last time when the Berliner Ensemble visited Bergen International Festival with an astounding performance based on Shakespeare’s Sonnets, and we witnessed it in the EDDA performance at The Norwegian Theatre.

Some may also have experienced the ground-breaking opera “Einstein on the Beach” from 1976, created in collaboration with Philip Glass.

As the lecture goes on, I gradually get accustomed to the repetitive text patterns and surrender to the meditative atmosphere. I enjoy a lecture based on a text that is both charming and amusing, as well as thought provoking on a philosophical level.

Cage talks about tradition, about the old music which he is about to leave behind for the sake of something radically different. Still, tradition is precisely what he loves, just like Arnold Schoenberg, another of music history’s great innovators. They both find their own voice, but in very different ways. Cage speaks enthusiastically about Grieg’s music in his lecture, which we obviously find very pleasing here in Norway:

“I realize that I began liking the octave. I accepted the major and minor thirds. Perhaps, of all the intervals, I liked these thirds the least. Through the music of Grieg, I became passionately fond of the fifth. Or perhaps you could call it puppy-dog love, for the fifth did not make me want to write music: it made me want to devote my life to playing the works of Grieg.”

Is there any meaning in Cage’s lecture, which sometimes may seem like pure madness? I honestly do not know. There might be a number of meanings in the text, not least meanings one makes up oneself while reading it or experiencing the theatre version. Neither Cage’s text, nor Wilson’s theatre create a linear story; the artists do not offer a coherent and logical narrative with a beginning, middle and end.

The audience is left to make its own sense of the madness. This contributes to stimulating curiosity, and makes it impossible to remain neutral to the scenographic expression. As the American critic Mark Swed writes about Cage’s work: “by reducing everything to nothing you begin to understand that art is the experience of the moment, that all that matters is now. You can never possess art.”

Robert Wilson in “Lecture on Nothing” by John Cage, performed at Festival dei2Mondi, Spoleto, Italy, 2016. Photo: Lucie Jansch

At one point in his lecture, Cage writes that it is perfectly OK to sleep if you feel drowsy. Which is a liberating comment; how often has one not fought against drowsiness during a performance or concert? According to Cage this is not necessarily something we should criticise. This is delightful and liberating.

As Wilson is reading what Cage writes about it being perfectly OK to take a nap during the performance, he gets up from his chair and walks over to a small bed on the other side of the stage. He pulls the cover over himself, closes his eyes and seems to be sleeping for a little while. While he sleeps, we hear a recording of Cage’s own reading of the text. Wilson mimes the text in theatre’s language form, while respecting the importance of the pause. This does not give any immediate meaning – of course.

In his lecture, Cage writes: “All I know about method is that when I am not working I sometimes think I know something, but when I am working, it is quite clear that I know nothing.”

Back to the theatre. I decide to let my travelogue with my impressions and reflections veer off a bit and I introduce a secondary theme more closely connected to a reality we are familiar with in Norway as well, and which includes the repetitive occurrences when sitting in the auditorium as part of the audience. The Chinese lady in front of me takes out her mobile and runs her own text messaging show. That is when I do something not at all in the spirit of Cage: I tap the lady on the shoulder and ask her to please turn off her phone. She stares at me open-mouthed, as if I just fell from the moon, and keeps on texting unperturbed.

It occurs to me that this lady is not the only one in the audience glued to a phone; there are hundreds. As a stranger, I choose a sensible and pragmatic approach; I lean back and sink deeper into my chair. I realise that the mobile flash symphony does not really matter as the repetitions on stage lets me flitter in and out of the performance as I wish anyway.

In the middle of this Chinese turmoil I come to think of the debate in the papers back home in Bergen concerning how to behave at the concert hall. Is it, for instance, acceptable to bring a glass of wine into the concert hall Grieghallen or not? Influenced by Cage, Wilson, and the many Chinese people around me, I find the answer: A glass of wine is perfectly fine as long as you show consideration for your fellow members of the audience.

But were things not better in the good old days, when the performances were predictable, when the audience showed good manners, and peace and order ruled in the auditorium? No. At the beginning of the 19th century, to move to and fro during the performances was the most natural thing in the world for the Italian audience; they had a cigarette and drank a glass of wine, or several, while chit-chatting constantly.

Another example is the outdoor promenade concerts becoming indoor concerts in London towards the end of the 1830s. Not to mention Lumbye’s concert hall in Tivoli in Copenhagen, where people were smoking, drinking and eating cake during the concerts. Such were the circumstances all over Europe during the second part of the 19th century, which means that the music was only one part of the experience. Take composers like Rossini, Donizetti and Lumbye; they were all used to the audience engaging in other activities than listening.

Only in recent times have the audience been trained to sit in dead silence and look down on the next person if he or she, like some impudent barbarian, should for instance do such a thing as applaud between the movements of a symphony.

Cage’s and Wilson’s liberal views, their curiosity and anti-authoritarian attitudes are appealing. The normally rather well-adjusted Chinese enjoyed the aesthetic-free zone at the theatre and behaved like a 19th century European audience. Which suited Cage’s lecture very well. Maybe we have something to learn from the Chinese’s uninhibited way of experiencing art – even though it is not very popular in today’s western world to talk about decorum and refinement in connection with visits to the theatre and concert hall – as the idea of what is decorum and refinement has undergone such great changes.

On a more intellectual level refinement was once about transcending yourself, about refining yourself by utilising your full potential – not least through experiencing art and engaging in a dialogue with others about art. In this perspective, art performances were a very serious matter. Now, we use art widely as entertainment. We consume more art and culture increasingly, but we perceive art and culture decreasingly as something which reflects our common social and human conditions and instead as something that in essence contributes to our contemplation of what our common reality has become, and why.

Initially it may seem that Cage and Wilson are boosting this prevalent development. But, we soon discover that what they are actually doing is stirring up thoughts and ideas about what part art plays and should play in our society and civilization.

LECTURE ON NOTHING

John Cage (1912–1992), American composer. His music and philosophical poetry has had great influence on the development of modern music since the 1940s. Cage’s “Lecture on Nothing” was printed the first time in his first and most important publication Silence from 1961. It consists of zen-like aphorisms and observations and what is almost an obsession with repeats.

Robert Wilson (1941–), American stage director, scenographer, and visual artist. With his epoch-making theatre concept, Wilson is considered one of the 20th century’s greatest stage artists. Wilson's staged version of “Lecture on Nothing” was performed for the first time at the Ruhr Triennial in 2012, focusing on Cage for the 100th anniversary of his birth.