Rejoicing to Heaven, Grieving to Death

- Home

- Festival

- 2020-and-before

- Articles

- Rejoicing To Heaven, Grieving To Death

- By:

By: Anders Beyer,

May 03, 2019

“She is the one who stays, but also the one who gives, while the one who leaves is the one who takes.” A conversation with Karl Ove Knausgård, 8 February 2019, in London.

Anders Beyer: You have recently written an essay about how you found your voice and started writing. Can you expand on that?

Karl Ove Knausgård: It’s about creating a space where it’s possible to say something. For me it’s very much about a kind of emotional truth. Everything is emotionally charged, philosophy too. A great deal is missing for me when I read philosophy, or when it’s supposed to be about existential questions, and the reality isn’t involved, the space we live in. The quite simple and banal things, or things that are just silly, they have to be said too, since that can give life a kind of weight, a new truth. I already knew when I began to write that this is what it’s about, this is way it is.

But it’s difficult to write. You have so much to say, and then nothing seems to come. But suddenly there can be something that opens up, and then you can say everything. The truth may still be relative. My truth doesn’t have to be everyone’s truth. But it’s possible to say something true.

AB: What made you think you had to do just that: write?

KOK: I read a lot when I was growing up. For me it was very natural to think that was what I should do, that I should write, as I had such great experiences in connection with literature while growing up. When I was 16, I began reading books by Hemingway for example (The Sun Also Rises) and Jack Kerouac, which made it cool to be a writer, more of a lifestyle and a way to be; that’s what was interesting to me.

AB: You also thought about becoming a musician?

KOK: Yes, but if a writer was what I became, it was very much because I wanted to be a writer. I sort of had nothing to say or anything like that. But something happened when I began on my first novel at the end of my twenties – reading and writing became more or less the same for me, they fused together. Then a space arose that I could go into every day, and be in and come out of, which wasn’t me but which wasn’t out there either, it was somewhere in between. It was very much about disappearing into it and about creating, about something being created there. I suppose I had experienced it in flashes when I was in my teens and wrote, but never that way. This is what I always try to get back to when I write. I don’t write because I want to say something in particular or because I want to do something important. I write because I want to be there. There, everything that is important comes out. But it isn’t such that I go around thinking that I have to write about this, or that now I have to write.

AB: So what is important comes, and you write about what you experience as true. The starting point is often the personal, your own reality. Is that where you find the fuel for your writing engine?

KOK: No, but I appreciate what you mean. That’s what is so treacherous; it’s so easy to think that writing is a self-absorbed activity, or that it’s about your own problems, that it’s the place you have to go because it’s the only place the writer really has access to. It’s the individual viewpoint, it’s the subjective, it’s where you see the world from, you can’t see the world from some other place. But then the thing about literature is that it’s collective after all, it’s for everyone, relational. That’s what makes literature so special, for the moment you begin to write literature, it’s no longer about yourself or about your own problems, it’s about something else. It’s as if you latch on to something else that is much more, you get into a current that has flowed there for hundreds of years and that you become a part of. But you so clearly use yourself and your own experiences to get in there, for you have no other experiences, they don’t exist. I can’t think of a writer, or an artist or a composer, who doesn’t use himself or herself to go there.

AB: You experience that you come in and sort of become part of a current, of something that has been there for an endlessly long time?

KOK: Yes. And that’s exactly the same as you do when you read. You become part of a flow that exists everywhere around us and has been going on since time immemorial. When you write, that’s also what happens.

AB: So you don’t think there’s such a big difference between being a reader and being a writer?

KOK: No, I don’t think so. When you read, in the best case you disappear completely. When you write you also disappear completely in the best case. And then there are areas in between, of course, When you write, it’s as if you make your own choices, you do it this or that way because you think it’s best, but the reason you choose exactly what you choose is that there has been a huge amount of literature before you and behind you that makes it possible to go there or there. In a way it’s as if the more you’ve read, the more you’ve taken in something from others. The more unoriginal you are in a way, the more personally you can write and do your own thing as a writer, I think. But this is maybe both true and not true.

AB: During the reading of the first volumes of My Struggle, it becomes clear that you very much want to be recognized. You want to be successful and become known. You had problems at the writing school, since there were some people who wanted to control you too much, and you had difficulty finding your own voice. But little by little you found it. Both in your books and in the way you are as a person, I experience a great humility, which makes you always try to understand the surroundings. But in parallel with this there’s an element of megalomania. Can you say something about this?

KOK: To be able to say or write anything at all you must have self-confidence one way or another. Just having to hand over a novel to someone, to my editor, is a huge step. Why should he read it, why should I have something that others want to read? It’s a quite absurd and quite terrible thought, actually. All the same I’ve always done what I’ve done with an inevitability, while at the same time I seem to have had no self-confidence at all. I still don’t, although I’ve had lots of success. When I write a text now, I send it to my editor in exactly the same way I’ve always done, and think: this is quite hopeless, this is terrible. That’s how it is every single time, every single day. So that’s one side of it – yes, I don’t like myself, I don’t like what I manage to produce. At the same time I have an opposite side, since I also think what I do is quite fantastic. This is probably a quite simple psychological mechanism.

AB: On the one side, on the other side. If I had to compare your magnum opusto something, it would have to be Wagner’s Ring of the Nibelung, Stockhausen’s Lichtand Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, works that took several decades to write. It’s as if that was the format you decided on?

KOK: But it was exactly the opposite I wanted. I thought, now I’ll have to write something small and stupid, now I’ll write about my own life, and it mustn’t be big, it mustn’t be great literature, it must just be simple. It was only then I began to write so much.

AB: And My Struggle developed into a gigantic work.

KOK: Yes, but it’s small, even though it’s long. It isn’t big, because it’s only about one life. I’ve always thought of it as small, never thought of it as big. But it is long. What made it possible was that I didn’t think about writing great literature. My problem now is that I have to write great literature, and that won’t work, it’s quite impossible. So I have to get back to where I was, and just try to sort of scribble something down on the page.

AB: So the triggering factor was that you just managed to get writing?

KOK: Yes, that was the triggering factor.

AB: That you discovered that you should just get going and write?

KOK: Yes, yes – not make something, it didn’t have to be anything. I just had to write. That’s how it was.

AB: When you had finished the major work, were you firmly resolved not to write any more?

KOK: Yes. But there was a kind of loophole I had. Since I wrote about myself, and since it became so long, I had to find a way out, and that was the way out.

AB: What significance does your reading of Proust’s In Search of Lost Timehave?

KOK: I read Proust for the first time in the summer I turned 25, in Bergen. I was a student and had little money, and since his novel series was on sale, I bought it. I remember I sat out on the wharf and drank water in the café there and read Proust throughout the summer – that was what I did that summer. I thought it was quite fantastic. It was as if my childhood experiences disappeared into Proust’s novel, and I just wanted to be there. I read and read. At that time I couldn’t write.

But two years later I could suddenly write, and then I wrote a novel. I never associated the two things with each other, but now I do; now I see how much I learned from Proust, how much Proust there is in my first book; not in My Struggle, but in the one called Out of the World. I seem to have taken it all in, absolutely everything, quite uncritically, and then just poured it out again, entirely without knowing it. The whole understanding of time and space, and the whole architecture of the novel, where a metaphor can sort of build one space here and another space there, and where the past, future and present are also spaces in a kind of novel architecture, I just took that straight in without knowing it came from Proust. So he has meant an incredible lot.

But when I wrote My Struggle, I thought that wasn’t how I would do it, for I knew after all that it was autobiographical, so it had to be quite different. No metaphors, not that type of construction, not the elegant and sophisticated type either, but much, much simpler. And now I seem to have exhausted that possibility. I could have spent twenty years writing In Search of Lost Time all over again, and might have written a fantastic book, but I can’t do that any longer. And it became what it became.

AB: You have said that your subject or your ideas must come to you unawares. What do you mean by that?

KOK: It’s difficult to formulate, But I’m not interested in what I can do and what I know because I can do that, and I knowthat. I’m not interested in showing off what I can do, for then it’s already finished, but I’m extremely interested in what comes into existence while I’m writing. And I think there’s an energy for the reader too in the fact that the writer in fact doesn’t know where he’s heading, that there’s a kind of voyage of discovery at the same time, where you feel that you’re seeing the world in a new way or from a new angle. What is so nice is that it’s fine to write about yourself and not know what will come on the next page, not know where it’s all going.

I think we have a version of ourselves that is quite fixed. If you have to introduce yourself, you’ll say that you’re called this and that, you work with this and that, you grew up there and there, your dad was like this, your mum was like that. Then you can expand on that, but there’ll always be something tangible that is your character, that is your identity. And that’s quite OK, that’s what you live with every day and think about yourself. But you’re so incredibly much more than that. And one way to get hold of it is to begin to write about yourself and just see what pops up, instead of sticking firmly to this or that identity. For example you can write very close to a particular day about what happens in one day, about all kinds of thoughts and feelings that come up, so that who you are in a way loosens up a little. But you can only do that if you don’t know in advance what you want and where you have to go; you can’t plan it. If you plan it, you shut it in. What you are interested in is opening up.

AB: So in principal anything can be done, and new paths can arise without you actually knowing that it’s happening?

KOK: I can also write for example about an episode I’ve written about before, but begin in a different way, and then disappear into it. Then it’ll be different, will be about other things. This is the opposite of having a plot. With a plot it’s a bit the same as with an identity; it shuts the writing up in something in particular and in a given pattern. We see the world in categories and in boxes, and we have to do that so we can live here and get through it and handle it. But actually these are just our inventions, for in reality everything is very fluid and chaotic, and in a way I always think that’s what I have to get into when I’m writing. I never get in there in an elegant sort of way, but the fact that there must be something, a window, into what I don’t know anything about, is what drives me on.

AB: A few years ago something came to you unexpectedly that you couldn’t predict; that is, an approach from the Festival in Bergen about something you hadn’t tried before.

KOK: Wow, was that so long ago?

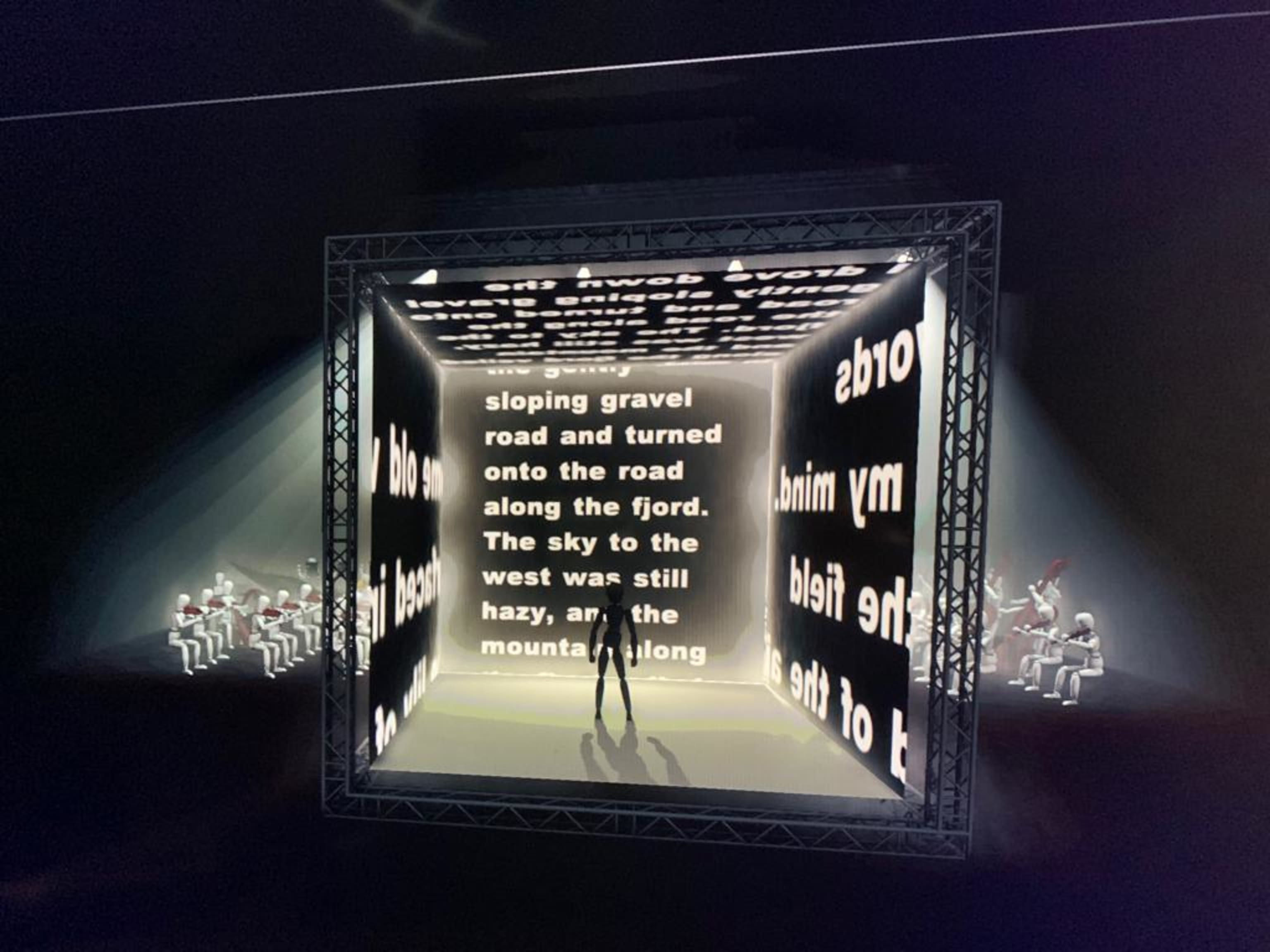

AB: I asked you whether you would write a libretto for a stage version of Grieg’s Peer Gyntsuites for orchestra. The idea was to create a kind of symphonic passion in a dual sense of the word: suffering and strong emotion, and wanted to focus on Solveig, not on Peer. Tell me a little about how you received my proposal, and about how you got started with his work.

KOK: I like Peer Gynt very much. That was the first thing, and I came to think about Tom Stoppard’s film Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, which is about the two secondary characters in Hamlet. You hardly see the action itself, for it takes place sort of somewhere else. When I got the proposal I had the feeling that one could go into Peer Gynt, but be inside Solveig, and then everything would look different and change the whole play in some way. It was almost a spatial understanding of it, and I thought it could be fun to try that, so I said yes.

I was given deadlines but couldn’t write anything for a very long time. Then I met the director Calixto Bieito. He said what he wanted; he wanted a monologue by a woman, but didn’t want it to be Solveig, and it shouldn’t be Peer either; it was to be a woman who is waiting, just as Solveig waited. And he said: “You can write as you want, write as you usually do, as you always do. I don’t want a text that rhymes.” It was very liberating that I could just do as I usually do. I had an idea that Solveig in Peer Gyntis someone who stays where she is and shows endless forgiveness and endless patience, which for me is very much a mother’s kind of love. She is the one who stays, but also the one who gives, while Peer, he is the one who leaves and the one who takes. That rhymed in Norwegian – I hadn’t thought of that. That was the second thing I thought of.

At the same time I was in New York, and I began to read a Kierkegaard text of all things: “The Lilies of the Fields and the Birds of the Air”. I thought it was a quite fantastic text, and then I thought that it’s about being exactly where you are, that life can be quite insanely rich and intense and meaningful here and now. The question on the whole isn’t what you do or where you go. What it’s all about is a sort of approach to the reality you have. You can sit here or there and live a totally valid life. I had a lot of thoughts like this. And then I thought about what it is she should talk about, this woman. After that I thought I should just let her sit and think about Søren Kierkegaard, and that should be my text. But then there was the other matter about giving and forgiving, and I asked what it really is, to give and forgive. So I was suddenly in a situation with a woman with her mother on the one hand and her daughter on the other – three women.

AB: It became a novella, a family saga?

KOK: Yes, and it became a novella that is about three women, where the youngest, the Solveig character’s daughter, is just expecting, and the third, her old mother, is waiting for death, while she herself, in the middle, is in a waiting relationship with the other two. It’s sort of three different ways of waiting. It’s the Solveig character who is giving, but that doesn’t really help. There are no limits for someone who gives – giving is a boundless activity. Now it sounds as if this is very big, but it’s very small. It’s a little story about three women.

AB: Why should the Solveig character work in the health care sector? Should we regard her as a kind of Florence Nightingale?

KOK: All I was thinking about was giving. That’s what I was thinking about. And that those who give are not seen, but those who take are seen.

AB: At one point in the novella Solveig says that she came to think about Kierkegaard. She says that she was on a Kierkegaard course in Lystrup in Denmark. For me that is such a presence that I almost feel I’ve been there. Do you know whether such a place exists?

KOK: No. But my mother is a nurse, and I remember that in the 80s and 90s there was a lot of talk about Løgstrup and Denmark, and Heidegger in fact, in the nursing sector. My mother started at the university and talked about it. So I had Løgstrup and Denmark in mind, and then I also put Kierkegaard in it, and so it became an echo of the 80s and 90s, nursing, Løgstrup, Denmark and Kierkegaard. Then it all fitted, and that’s what it became.

AB: When your Solveig figure had read Kierkegaard’s text, she felt as if she was standing at the edge of the kingdom of God, you write. In connection with your novella, as with several of your other texts, I’m reminded of a formulation in a Goethe poem:

“Rejoicing to Heaven, grieving to death,” I think it can be translated. I think your text lives and breathes in such a tension between the exalted and the everyday and trivial, with melancholy undertones. Do you recognize yourself in what I’m saying here?

KOK: Yes. What I’m trying to do is challenge the space I feel I live in, and have always lived in, which is the very trivial one. Where the fantastic only exists as some sort of construct, or in texts you read, and that you try to integrate. You try to get the sacred into your life. That was a feeling I had when I read Kierkegaard, the feeling that life can open up totally. That’s something very radical in Kierkegaard and in religion, which there’s a little of in my text. But it’ something I want to try, going into that space.

AB: Kierkegaard’s text takes on great significance for your novella, it’s quite central, and it has given you the title.

KOK: Yes, what I really want in my text comes from Kierkegaard, for whom I sort of make a space. And I want it to be true. I try to say it in a way that makes it true.

AB: So Kierkegaard becomes a kind of recurring motif.

KOK: Yes, he does. But his text is very strange too. It’s a sermon, it isn’t a philosophical text, but a sermon. It’s quite fantastic. I can’t say why it’s so fantastic. But when I begin to talk about it, I get tears in my eyes. There’s something incredibly appealing in it, with the lilies in the field and the birds in the air appearing again and again.

AB: How did you arrive at the title?

KOK: It says what my text is about.

AB: You listen to music when you write, can you remember which music you listened to when you wrote this text?

KOK: I listen to pop music when I write. I always play the same record – for three months at a time it’s the only one I play. I’m quite sure I played Father John Misty, his last album, when I wrote the text we’re talking about.

AB: So music is a kind of backdrop for you? How does it inspire you?

KOK: When I began to write, I put very loud music on – sort of to get into something else. I don’t do that anymore, now it’s a lot about feeling safe. Writing is about getting into something that’s a little unsafe, and maybe a bit dangerous. With the same music all the time it’s like a house I’m in, like a home. I get up in the morning, put on the headphones, then the music comes, and then I’m home. Then I can do anything I want, since it isn’t so dangerous any more. There’s some safety in that.

AB: Maybe you also want to shut something out? The noise that surrounds us?

KOK: It’s very much about making a space that is my own.

AB: The text, as we have discussed before, is about human relations and giving. But also, about humanity’s place in a larger context, in Nature, in the Creation, about the transitory and the new life that arises in defiance of normal programming. But perhaps it’s also about human limitations, about what normal Scandinavian life has become in the 150 years or so that have passed since Ibsen’s drama was written. Can one say that you make Solveig into a present-day character?

KOK: Yes. I take her qualities. There isn’t so much about Peer Gynt in my text, it’s Solveig’s qualities I transfer to our time.

AB: So the postmodern Solveig isn’t sitting waiting for Peer? She’s the mother of her child, and she helps he daughter and her mother, while at the same time she has to take care of her professional work. Can one say that your Solveig figure is in a process of becoming, while Ibsen’s Solveig has been deprived of her own existence?

KOK: That depends on what you mean by being deprived of your own existence.

AB: I mean that she has more or less deposited her creative energy with Peer, and just waits.

KOK: Yes, yes, that’s true. But at the same time, in the purely literary sense, you remember Solveig just as much as Peer. Peer saw clearly too, but Solveig in particular did.

AB: The personal, or autobiographical if you like, is often pivotal in your texts, but here it seems to be absent.

KOK: I’ve been very interested in what happens when you write “I” and are someone else. In whether it works to come out of yourself, especially because I’ve written so much just about myself. In a way this new text has been a little experiment for me. But what I wanted wasn’t to try to think like a woman, to create a woman. My thinking was: OK, here I have a situation with a main character who isn’t me. But at the same time I’ve used my own self, sort of poured in the other self and thus made something happen.

What I was wondering about was credibility: is my Solveig character a credible woman or not? I still don’t know. After all she isn’t me. All the same there’s a lot of me in her, obviously, and a lot of me in the text, but the purely factual has been taken out, so it isn’t so easy to see. Emotionally, it’s just as much there. And then there’s the way I write, for I write just as I always do. That’s why I wondered what it would be like when it’s a woman who writes like Knausgård – what would people think? I don’t know, but it isn’t me, that’s obvious, that’s what writing is. It wasn’t me either when I wrote My Struggle. It was bits of me, but it wasn’t me...

AB: What I think is so inspiring when I read your texts and other great literature, is that there are always some secrets there, that the text never reveals its inmost being, but remains enigmatic. I came to think about the brooch in the drawer of the woman who is waiting for death, and picked up several associations, for example with Munch’s painting The Brooch from 1903, one of his most beautiful and most acclaimed representations of woman. The brooch takes centre stage and creates a fine balance in the picture, emphasizing its mysterious aspect. What does the brooch mean for the woman in your text?

KOK: I can’t really say.

AB: But it means something?

KOK: Yes, obviously it does. But it’s not a riddle, there’s nothing in the text to be solved, there really isn’t.

AB: The reader is left unresolved, you could say.

KOK: It’s often like that in the world too, there are very many things that are not cleared up and resolved.

AB: Has the novella given you any ideas for further writing?

KOK: Yes, yes. Absolutely. There’s something there I want to go further with. Not least the thing with the birds. A friend of mine who is called Stephen Gill and lives in Sweden in the village where I have lived, is a photographer. He’s had a project going for two or three years where he’s been photographing birds. He sticks a pole in the ground and a camera with an automatic motion-triggered shutter release right beside it, and then birds start coming down from the sky – all sorts of birds. He gets quite fantastic pictures, and one of them is in my novella, the picture of him when he sticks a pole in the ground and attracts the birds down from the sky. This is something I’ve thought of going further with.

AB: What interest or energy is involved in this stuff with birds?

KOK: For me the magic is in the fact that it’s so exceptionally specific, so exceptionally physical – it just is. It’s so extremely material, it’s worldly, or earthly, it’s flesh and hunger and survival. It’s existence, the struggle to survive and all that – while at the same time there’s a kind of metaphysical sky above it all, which the birds are part of. I always want to penetrate to the real, the way things actually are, the way the birds actually are. And the way life actually is. We humans are also physically specific, fleshly creatures. But at the same time we live amidst all the rest. I’m very interested in these two levels – they always meet. They also do so in both Kierkegaard’s and my own text: Kierkegaard’s birds and the birds of the Bible, Stephen Gill’s birds and the birds of reality.

AB: And now you’ve handed over your work for someone else to do something with it. How do you feel about that? You don’t usually hand over a work that way.

KOK: When I delivered this text, I thought maybe the director couldn’t use any of it, and that it will be Solveig and songs and a setting he creates out of his own mind. Or maybe he’ll use some of it? Then my text will be a kind of echo in what he wants and in what he creates. I’m very, very excited about what the director will and can use, and how he sees it in his own setting. Here I have no prestige, I’ve just written the text, it was interesting in itself, and very fruitful.

AB: Now we’re talking about Calixto Bieito. And he’s given you some feedback. What did he write to you?

KOK: My impression was that he liked it and was moved by it, but that so far he didn’t know how he was to use it. But he’s used to taking texts that exist and working with them and making something of his own out of them. That’s what he does, that’s what directors do, and to be exposed to this is quite simply a privilege.

AB: So you don’t see it as an intrusion?

KOK: No, absolutely not. I have no ownership of what I have written. You can’t have that as a writer, for people read it, say what they like about it, think what they like about it, and write what they like about it. There have been dramatizations of my books that I’ve never read and never seen. I’ve said, do what you want, it’s quite fine with me, it doesn’t matter. After all it has to be alive. The more rules you have the less alive it becomes. It will be really intriguing for me to see how he can use my text. In a conversation he said, “You can write a whole life, you can write two minutes.” When I’m set completely free, then it‘s fun. And the same must go for him. He can use just two of my sentences if he wants, that’s entirely up to him. It’ll be exciting to see what he does.

Translation: James Manley