Solveig will wait no longer

- Home

- Festival

- 2020-and-before

- Articles

- Solveig Will Wait No Longer

- By:

By: Anders Beyer,

May 03, 2019

Karl Ove Knausgård has created a Solveig for today, and points to both Ibsen and Kierkegaard as well as the great in the small in his family saga

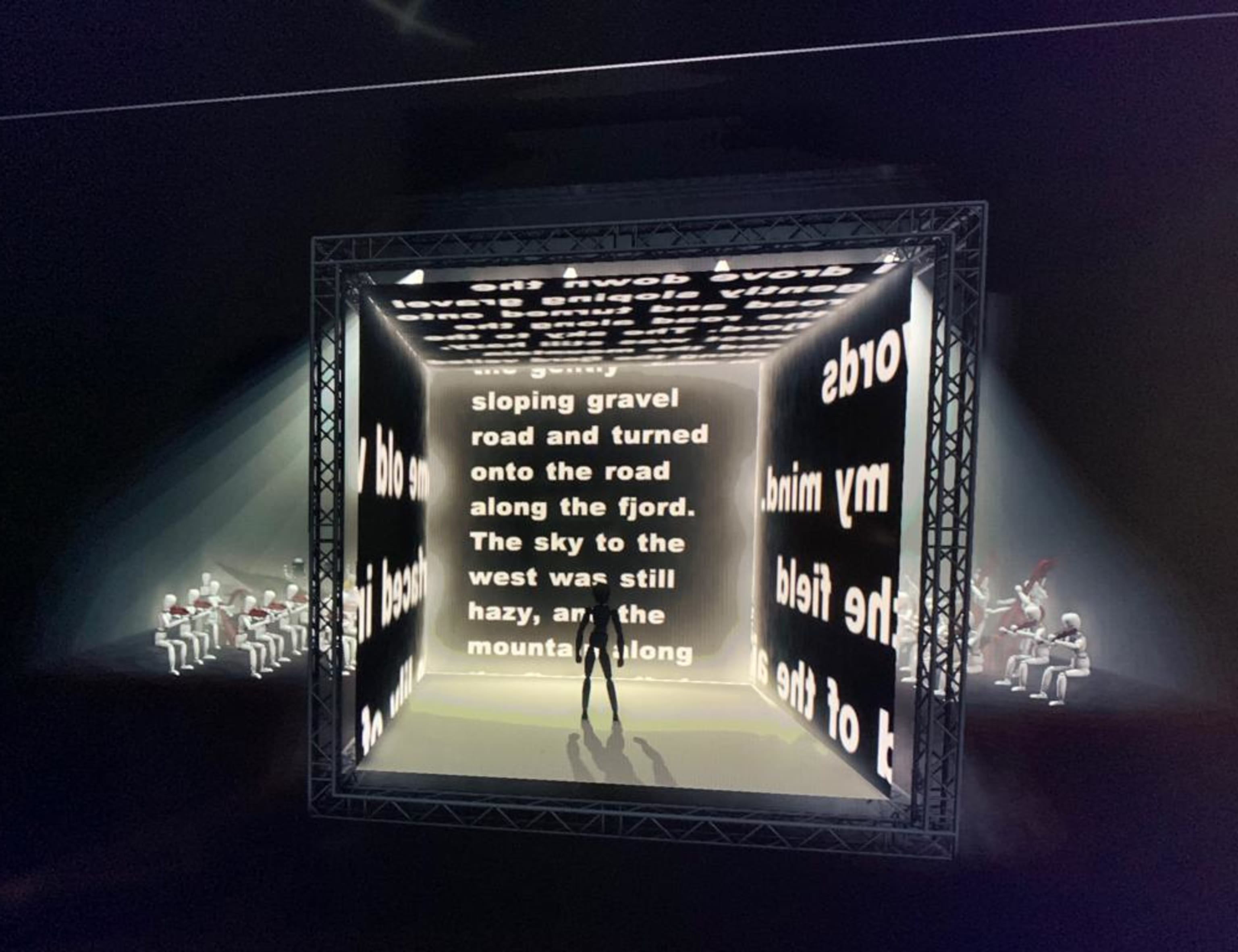

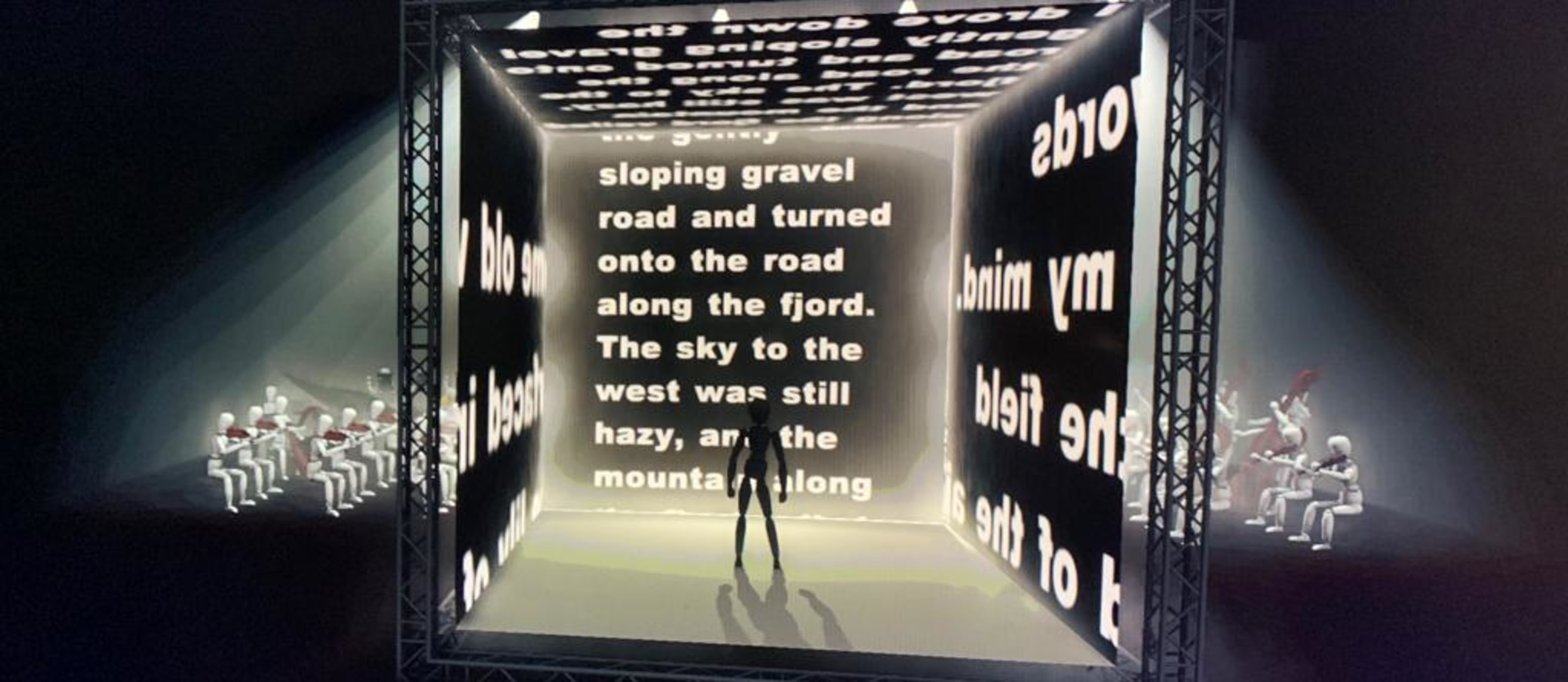

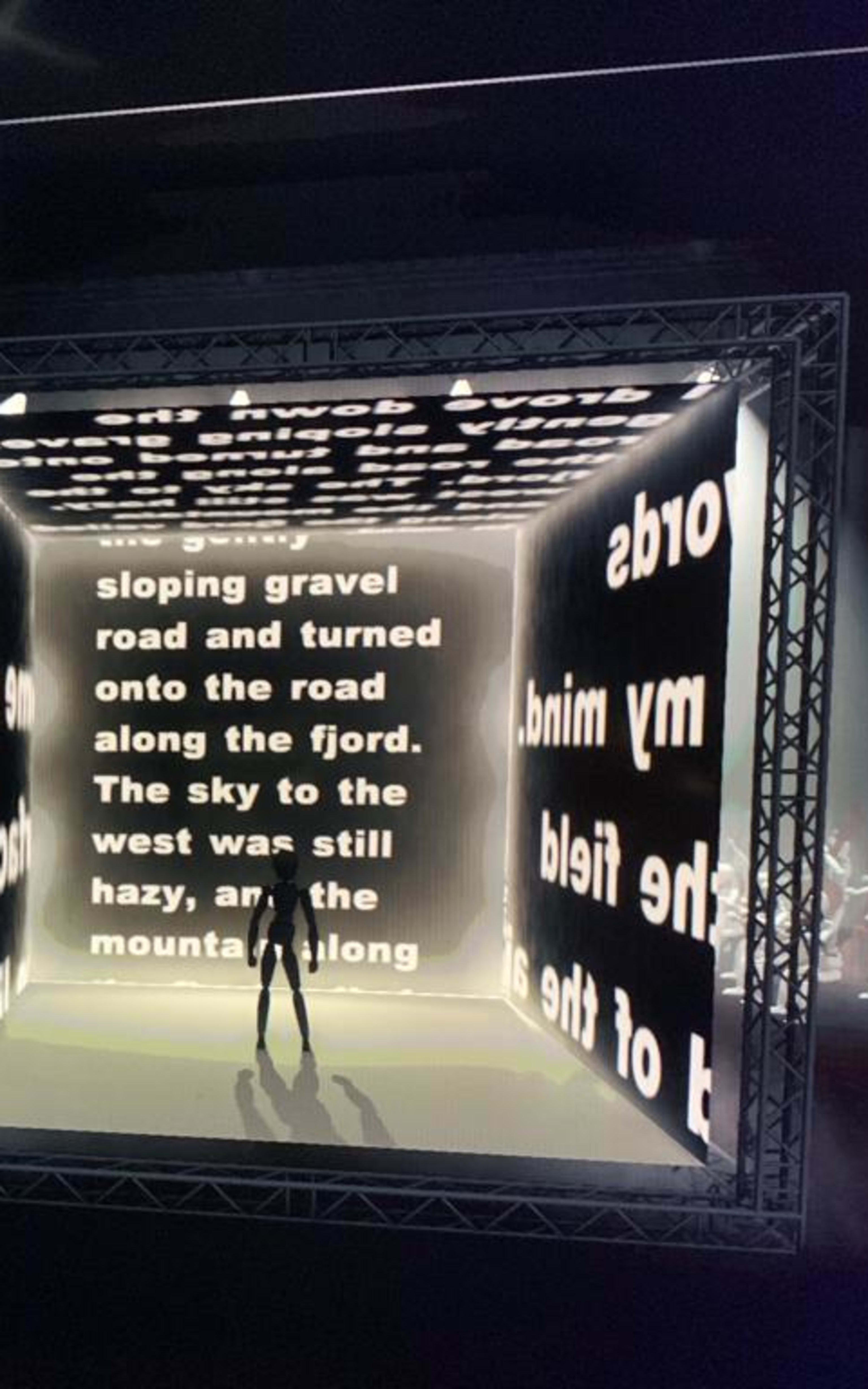

“Rejoicing to Heaven, saddened to death”, is a line from a poetic drama by Goethe. Karl Ove Knausgård’s writings live and breathe somewhere between the polarities of the exalted on one hand and the trivial and everyday on the other, with undertones of woe and melancholy. His text The Birds Beneath the Sky, written for the Bergen Festival’s opening production Waiting, directed by Calixto Bieito, is no exception. On the surface Knausgård’s short story is very simple – almost banal, some might say – although with Søren Kierkegaard as a recurrent motif and thematic guideline.

The Birds Beneath the Sky was commissioned as the libretto for a work that would engage in dialogue with Ibsen’s Peer Gynt. But it is not Peer who stands at the centre this time, it is Solveig; not Solveig as she is presented in Ibsen’s great drama; this is a female figure from our own time inspired by Solveig, with some of her qualities, especially her ability to give. No one can introduce the production better than the director Bieito:

“When I staged Peer Gynt, and a few years later the opera Hanjo by Toshio Hosokawa with a libretto by Yukio Mishima, I was totally fascinated by the two female characters Solveig and Hanako, a geisha, both abandoned by a man and eternally waiting. I was intrigued by their disappointment, their despair, but also by the profound love, tenacity and perseverance of the two women. The theme in Waiting is human loneliness – a loneliness from which no one can break free. It is also about the small details and the stories that make up our existence. The idea for this production was born many years ago out of boundless love for Solveig and Hanako, two characters who in my mind are real human beings of flesh and blood.”

The production takes the form of a symphonic ‘passion’ in a dual sense of the word: a tale of suffering and passionate commitment. It is based on Grieg’s Peer Gynt suites for orchestra and soloists, as well as some a cappella choral works by the same composer. There is only one soloist, Solveig.

When Knausgård took on the task of writing the libretto, he was given completely free rein. The result was a small novella encompassing a family saga. The first-person character, who is called Solveig, and who we associate for good reasons with Ibsen’s female character, works in the health care sector, takes care of her old mother and is confronted with the fact that her young daughter is pregnant. Solveig’s husband is absent. All three women are waiting: the eldest is waiting for death, the young daughter is expecting her child, and the Solveig figure has a waiting relationship with both. There are three different ways of waiting.

But Solveig is not only waiting, she is giving: she gives and gives. And according to Knausgård there are no limits for one who gives; giving is a boundless activity. In an interview published in an upcoming issue of Norsk Shakespeare- og teatertidsskrift the author says that Solveig, both in Ibsen and in his own work, is a figure who demonstrates boundless forgiveness and boundless patience, and these are capacities he associates with a mother’s love. We are looking at a major theme complex packed into a very small story.

As suggested, Kierkegaard is just as important a source of inspiration as Ibsen for Knausgård. During a stay in New York he happened to read Kierkegaard’s text The Lilies of the Field and the Birds of the Air (1849).

'I thought it was a quite fantastic text, and then I thought that it’s about being exactly where you are, that life can be quite insanely rich and intense and meaningful here and now. The question on the whole isn’t what you do or where you go. What it’s all about is a sort of access to the reality you have,' the author says in Norsk Shakespeare- og teatertidsskrift.

At one point Knausgård thought he should just have his Solveig sitting thinking about Kierkegaard, and that this was what should constitute his text. His title, The Birds Beneath the Sky refers directly to Kierkegaard. But he was unable to let go of the question of what it means to give and forgive, and so it became a story about three women.

After reading Kierkegaard’s The Lilies of the Field and the Birds of the Air, Knausgård’s Solveig feels as if she stands “at the edge of the kingdom of God”. Kierkegaard’s text consists of three sermons, which he calls “godly discourses”. They begin with a prayer in which mankind’s own responsibility and the options of the individual are emphasized. Kierkegaard wants to show “what it is to be human” in modern society, where “the human throng” and the collective pronoun man (= “one”), as the philosopher Heidegger says, predominate, such that the individual is diverted from the fundamental requirement, which for Kierkegaard is precisely “the requirement to be human” and involves the demand for silence, obedience and joy. This is something we must learn to live by. And how can we learn it? By observing “the lilies of the field and the birds of the air”!

Kierkegaard’s starting point is the Gospel of Matthew 6, 24-34, which says among other things (in the King James version):

24 No man can serve two masters: for either he will hate the one, and love the other; or else he will hold to the one, and despise the other. Ye cannot serve God and Mammon. 25 Therefore I say unto you, Take no thought for your life, what ye shall eat, or what ye shall drink; nor yet for your body, what ye shall put on. Is not the life more than meat, and the body than raiment? 26 Behold the fowls of the air: for they sow not, neither do they reap, nor gather into barns; yet your heavenly Father feedeth them. Are ye not much better than they? 27 Which of you by taking thought can add one cubit unto his stature? 28 And why take ye thought for raiment? Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow; they toil not, neither do they spin [....] 33 But seek ye first the kingdom of God, and his righteousness; and all these things shall be added unto you. 34 Take therefore no thought for the morrow: for the morrow shall take thought for the things of itself. Sufficient unto the day is the evil thereof.

Knausgård’s text only has indirect points of contact with Ibsen’s Peer Gynt. The connection with Kierkegaard’s “three godly discourses” is more evident, and through this Knausgård also relates to the Gospel text. But he is a long way from sermonizing or preaching. If God is also present in his novella, it is through Solveig’s reading of The Lilies of the Field and the Birds of the Air, and through her personality, the incarnation of love and goodness. God may be revealed, both Kierkegaard and Knausgård seem to be saying, in human relations and this can help us to understand that we are part of a greater whole, which is Nature or the Creation. And thus we can accept that our lives are transitory, and that death is a precondition of new life, which can arise in defiance of all norms and all programming, as in Knausgård’s text. It is all about mankind’s limitations, but also about mankind’s potential.

Knausgård’s postmodern Solveig does not sit waiting for Peer; she is a mother to her child, a helpful daughter to her own mother and has a job that requires a great capacity for caring. She acknowledges the smallness of mankind, but at the same time herself offers hope.

Translation: James Manley